A close-up of the Canby Family Chart—Quaker descendants.

Bucks County, PA

Their history of pacifism, equality, and tolerance influenced the course of events in early America. Today, millions can trace their ancestry back to the Quakers, possibly even you.

Download our research guide to get started

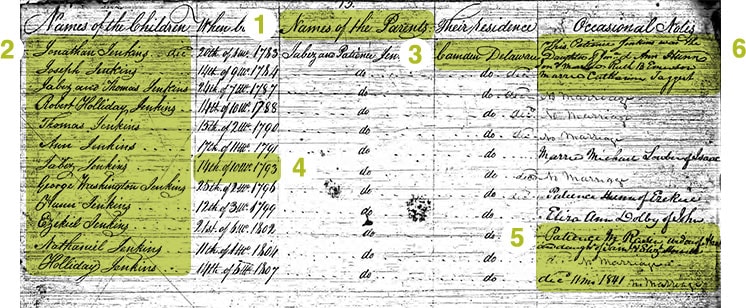

TIP 1: Birth registers identify parents.

TIP 2: Registers sometimes name each child in the family in succession. This usually happens if the births are being recorded at a later date.

TIP 3: Registers will often include place of residence.

TIP 4: Quakers numbered months rather than using the months’ typical names. So 14th of 10th 1793 would be 14th day of the 10th month, or 14 October 1793. (Also, Quakers did not change from the Julian to the Georgian calendar until 1752. So for years prior to that, first month meant March.)

TIP 5: Registers will often include comments referring to marriages or deaths of individuals listed.

TIP 6: You may find information about the mother’s parents.

Records for births of children in the congregation. Births are sometimes listed by date and sometimes by family group.

Names of children, birth dates and places, and their parents’ names. They may also include witnesses or the midwife.

Quakers started keeping records from their earliest years. Look for the parents in older registers or meeting minutes. You may discover another generation or two!

Some register books were created long after the births took place. This may have happened because the old book was lost, or, in the case of the Separation of 1827, when Quakers split into two factions and one kept the books, while the other had to start over from memory.

(Choose Birth under Event Type on the search page.)

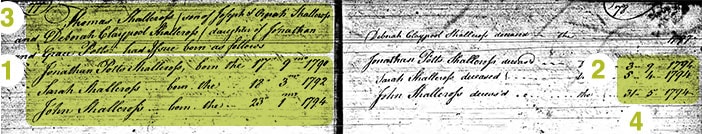

TIP 1: On the left side, membership records usually list the names of the parents, the children’s names, and dates of birth.

TIP 2: On the right side, you will see the listed dates of death for family members. In this tragic case, all 3 children died in the same year, at the ages of 4 months, 2 years, and 4 years old. The mother died a few years later.

TIP 3: Quite often, the grandparents' names are listed in addition to the parents' names, providing information on an additional generation. This information is only recorded in this type of record. It is usually not found recorded in the meeting minutes.

TIP 4: Quakers numbered months rather than using the months’ typical names. So 31 5 1794 would be 31 May 1794. (Also, Quakers did not change from the Julian to the Georgian calendar until 1752. So for years prior to that, first month meant March.)

Membership records are entries about the members of an entire family in a congregation. Membership lists can be a family history goldmine because they usually list three generations.

Names and dates of birth (and sometimes death), as well as family relationships.

If you are given the names of the grandparents, you may be able to find them in the meeting minutes. They will most likely be in the same meeting, or one nearby.

There will most likely be a mention recorded in the meeting minutes about the passing of deceased members of the family. Search for these by date. Look for requests for burials as well. Members were usually buried in the burial grounds owned by the meeting. However, keep in mind that in many instances, these records were written when a family moved into the area and joined the meeting. If this is the case, there won’t be a mention of the marriage, births, or deaths in the minutes of this meeting because they didn’t occur while the family was under the care of this meeting.

(Choose Member List under Event Type on the search page.)

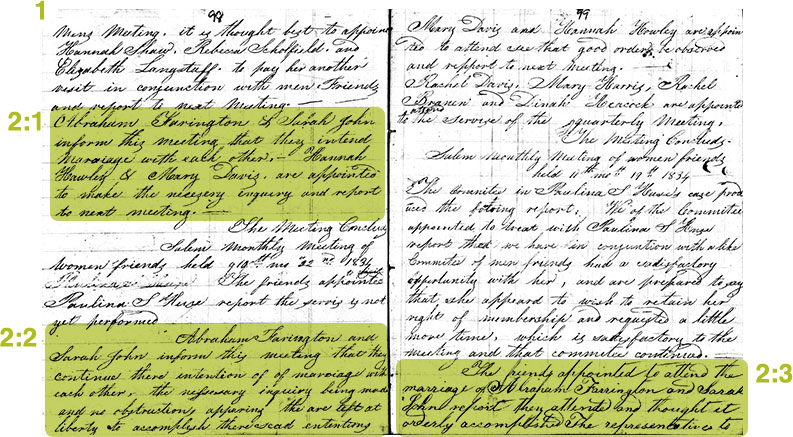

TIP 1: Meeting minutes were kept by both the men’s group and the women’s group. They usually include different issues that the groups discussed. The minutes were kept by one volunteer who was approved by the group. The same person often kept that position for several years.

TIP 2: In this case, we will use a wedding as our example. Meeting minutes will have entries for three consecutive months for an upcoming wedding over which the meeting has “care.”

Month 1: The bride and groom had to appear before the group and request that the meeting “oversee” the wedding. Two people are assigned from the “Overseers Committee” or “Committee on Oversight” to visit with the groom and bride in their homes and report back. The appearance by the bride and groom and the names of those assigned to visit with them are recorded in the minutes.

Month 2: The report from the Overseers is given to the group and recorded in the minutes of the women’s meeting. Often the minutes will indicate only that the couple are “cleared for marriage.” The two committee members are usually asked by the women’s meeting to continue in their assignment and attend the wedding and report back. Sometimes a Date of Liberation certificate was given to the couple, especially if they were going to be married later or elsewhere, indicating the date they were cleared by the meeting to be married.

Month 3: The third entry will be a report that the wedding was accomplished and the date. In the early years, the entire marriage certificate was copied by the clerk into the minutes, along with the names of all of the attendees who witnessed the marriage ceremony.

Records of happenings during a gathering of a Quaker monthly meeting.

Meeting minutes contain a recording of all business conducted in the meeting. This will include approvals of marriage intentions and records of discipline, disownment, and removal. Monthly meeting minutes rarely include information about births and deaths.

A search in the minutes will reveal that couples were sometimes disowned for “marrying out of unity.” Quaker couples who were in a hurry, or knew that they would be disowned anyway—for marrying a non-Friend, or a first cousin, or marrying without their parents’ consent—would often go to a priest to get married. Their marriage date will not appear in the minutes, but the name of the member will be found when disciplinary action is taken for marrying out of unity.

If a member of the meeting “married out” or married “contrary to discipline” to someone from outside the faith, the name of the spouse was not recorded, nor was the location or date of the wedding. So learning the exact circumstances surrounding an event may not be possible from meeting minutes.

The Quaker Collection on Ancestry.com marks the first time these particular records have been organized, indexed, and placed online. In order to best use the collection, you’ll want to understand the records and what you can expect to find in them.

There are two different applications of the word “meeting” in the Quaker religion. One is used to describe the congregation. Quakers first came to America in the mid-1600s, and they eventually organized hundreds of Quaker meetings, each of which met on Sunday morning for a worship service called “meeting for worship.” Some of these congregations were small, fledging groups organized under the care of a nearby, larger meeting.

The second application for this word is a business meeting held each month, called monthly meeting. It is the monthly meeting minutes that contain references to the early Quakers.

Monthly meetings were attended by representatives from meetings in their geographic area, which in some cases may be wide, depending on population. Monthly meetings sent representatives to quarterly meetings, which covered an even larger area and in turn sent representatives to yearly meetings. Yearly meetings are like an archdiocese, and their jurisdiction could cover all the meetings in or around a city (Philadelphia Yearly Meeting) or the meetings in a region (New England Yearly Meeting).

There are several types of monthly meeting records: minutes taken during men’s or women’s business meetings (they met separately); registers of births, marriages, and burials; and others such as disownments, marriage intentions, apologies, and memorials. Membership records were kept for families as long as they remained within the geographical boundaries of the meeting.

Have fun exploring the minutes of the meeting where your ancestors attended. Ancestry.com has indexed every name mentioned to make this much quicker and easier than ever.

Keep in mind during your search that your Quaker ancestor’s name may appear many times, or only a few times. It all depends on their level of activity in the meeting and their length of residence within its geographic region. For example: If they did not marry in that meeting, did not receive financial help or serve on any committees, had no children while living there, and did not die there, their names may only appear in the membership records.

For more information about who the Quakers were and the types of records they kept, you can also download our helpful research guide.

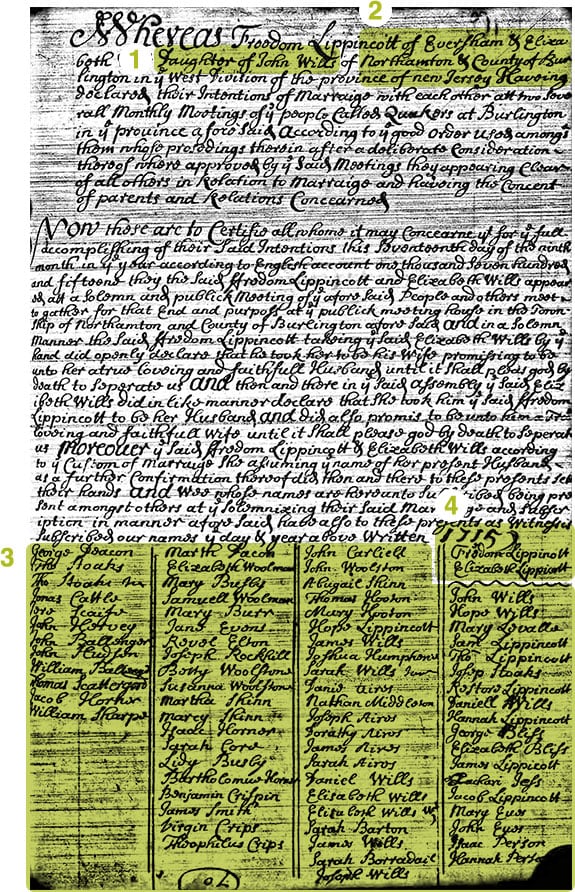

TIP 1: Marriage records usually include names of both the bride and groom’s parents and whether they are living or deceased.

TIP 2: Marriage records will indicate where the bride and groom are from and often where their parents are from.

TIP 3: All attendees at the wedding are witnesses and signed the marriage certificate as legal witnesses that the marriage took place.

TIP 4: Here you will find the date and the signatures of the bride and groom.

A Quaker marriage certificate is a legal document. It takes the place of a civil document and is proof that the wedding took place. Quakers were given special legal dispensations in England and America to marry their own. In the early days, meetings could oversee marriages only when the bride and groom were both members of that meeting (congregation) and where the meeting had entered the details into the minutes as proof that the marriage took place. All the people in attendance are legal witnesses and sign their names as such.

Among the signatures, look for names of family members, relatives visiting for the wedding, prominent Quakers, and even children.

Marriage certificates become treasured heirlooms in Quaker families and are often passed down through the generations. You’ll find many copies of certificates in the Quaker Collection on Ancestry.com, but keep in mind that these are not the originals. They were copied into the minutes by the clerk of the meeting. Eventually, clerks stopped including the names of all the witnesses because it wasn’t required by law, and it was laborious work.

(Choose Marriage under Event Type on the search page.)

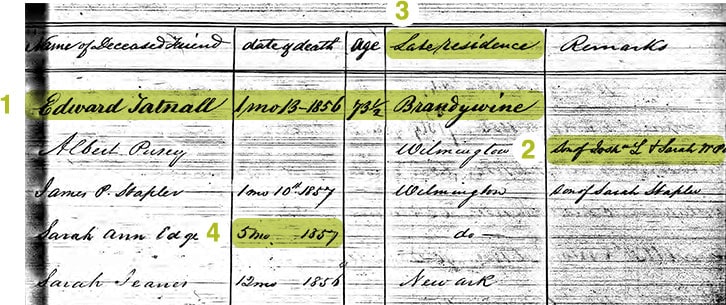

TIP 1: Death registers may provide the name of the deceased, the date of death, the age if known, and the place of residence.

TIP 2: Registers sometimes name the deceased’s parents, if known.

TIP 3: The term “Late Residence” was a term used in the 18th & 19th centuries to refer to the deceased’s most recent residence.

TIP 4: Quakers numbered months rather than using the months’ typical names. So 5 mo 1857 would be May 1857. (Also, Quakers did not change from the Julian to the Georgian calendar until 1752. So for years prior to that, first month meant March.)

Registers (books) with lists of deaths among members of a Quaker congregation.

Names of the deceased, the date they died, age of the deceased, and place of residence.

Look for a note in the meeting minutes about the passing of the deceased; you’ll usually find these somewhere near the date you see in the death register. There are often details recorded there regarding the cause of death, especially if there was a protracted illness.

You may also find a note in the meeting minutes regarding permission being requested (and granted) for burial in the meeting’s burial grounds.

(Choose Death under Event Type on the search page.)

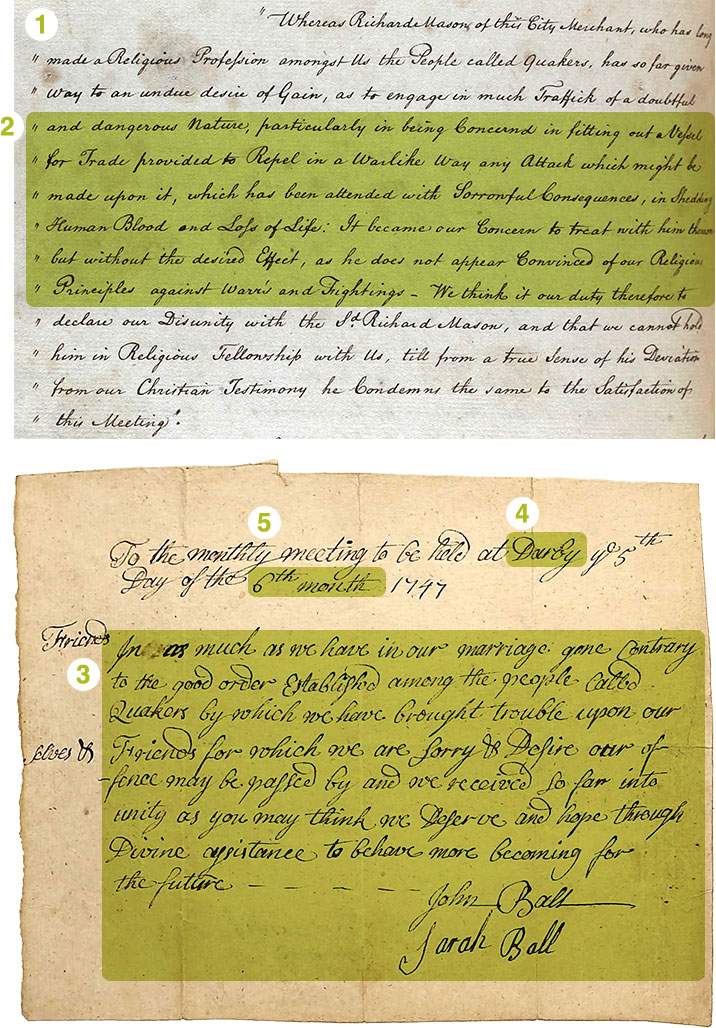

TIP 1: Disciplinary actions were formal procedures wherein an offender was counseled in private by a small group of Friends about offending behavior. If they were not willing to apologize, they were "disowned." This enabled Quakers to continue to love the “sinner” but hate the “sin.” The offender was not ostracized but was encouraged to come to a meeting, although he/she was not allowed to voice opinions in the business meeting. The act of disownment was a serious matter to Friends, not taken without cause or without a good deal of discussion. A summary of the discussions will appear in the meeting minutes.

TIP 2: Some of the offences for which early Quakers were disowned were in alignment with their basic tenets. Because Quakers believed that war and aggression were not the Lord’s way of solving any problem, Quakers such as Richard Mason, a merchant who outfitted a vessel for defense which resulted in loss of life, or those who went to war, carried a weapon, or helped with war efforts (making wheel rims or bullets), were acting against the Friend’s “Principles against Warr’s and Fightings” and were open to disownment as a result of their actions.

TIP 3: If the offending Friend repented, he/she was asked to write a letter of apology to the meeting acknowledging that the misdeeds were offensive to Friends’ principles and discipline. These records are called apologies or acknowledgements and will appear either in the meeting minutes or in separate books.

TIP 4: Look for the name of the meeting to find where your ancestor was living.

TIP 5: Quakers numbered months rather than using the months’ typical names. Also, Quakers did not change from the Julian to the Georgian calendar until 1752. For years prior to that, first month meant March. So this date of 5th day 6th month would be 5 August 1747.

Disciplinary actions were taken on occasion in an effort to define and reinforce the basic tenets of the religion. These included disownments, in which a meeting affirmed that it did not “own” the offender and denied responsibility for his/her behavior, and apologies, formal statements written to the congregation apologizing for offending behavior.

Details about the offence are sometimes included in the written statement. The details will not be found in the Hinshaw Encyclopedia because the individuals doing the abridgements were asked to keep all such details out of the Hinshaw notes. The offence will be found in the meeting minutes although the extent of the details will vary according to the discretion of the clerk keeping the records.

Sometimes meetings worked for years with offenders, resulting in multiple entries in the minutes. It is worth the time to read through all of them in order to get an accurate picture. Disownment was never final, although the passing of a year or more was the norm before an offender could apply for reinstatement. Once the sin had been repented of, it was supposed to be forgotten by all. Disownments were phased out in the late 1800s.

Quakers could face disownment for numerous reasons. These included theft, marrying contrary to discipline, gambling, public intoxication, and others.

(Choose Disownment under Event Type on the search page.)

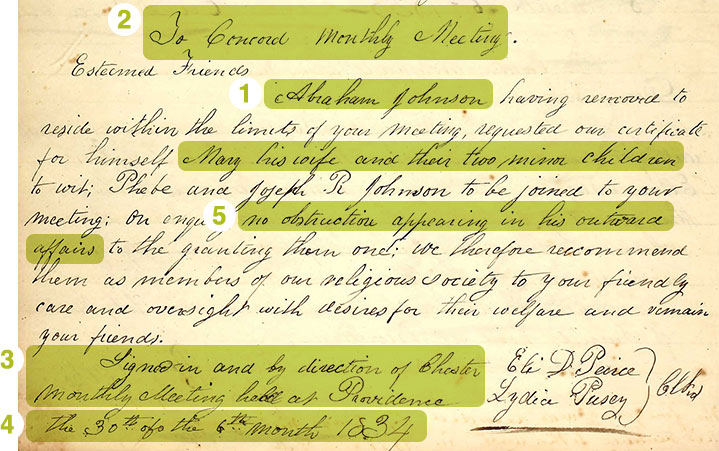

TIP 1: Look for names and family relationships. This certificate identifies a father, mother, and two children. It also notes that the children are minors.

TIP 2: The certificate is addressed to the new meeting, the destination this family is moving to.

TIP 3: The certificate is issued by the old meeting, the place the family or individual is coming from.

TIP 4: A date provides a time frame for the move.

TIP 5: The phrase “no obstruction appearing in his outward affairs” refers to the general financial condition of the family or individual.

A letter of transit for a person or family who is leaving one meeting and seeking to join another (removal is an English term meaning “to relocate”). The main purpose of the document was to assure the new meeting that new arrivals could be trusted and that their former meeting knew the family well enough to vouch for them. With this letter or certificate, a new arrival would be welcomed immediately to the new meeting and given any needed assistance in order to get settled.

The names of the current and destination meetings, a date, and the name of the individual or family moving. A family will list the husband and usually the name of the wife and minor children. A certificate of removal may also include a statement about the general financial welfare of the individual or family.

The information contained in a certificate of removal was written into the minutes of the former meeting when parties left, and when they reached their destination, it was entered into the minutes of the new meeting. However, not all meetings conformed to this practice at first. After about the mid-1700s, it is possible to track a family’s moves by reading their certificates of removal.

Removal registers, separate books tracing requests for certificates and approvals given, were kept by many meetings. In other meetings, requests and approvals are found only in the body of the minutes. Check for both possibilities by using the Browse function in the meeting minutes for the meeting where your ancestor lived. This will show you a list of all the record types available for that meeting. If there is no register of removals, then check the meeting minutes directly.

(Choose Removal under Event Type on the search page.)