Ancestry® Family History

Korean War

The Korean War (1950-1953) holds a distinct place in U.S. history as the first major conflict of the Cold War. On June 25, 1950, Communist North Korean forces, with support from China and the Soviet Union, crossed the 38th parallel into non-Communist South Korea. South Korea strove to maintain its newly established sovereignty with the help of troops from the United States and other United Nations allies, such as France and the United Kingdom.

Historically, the Korean War has often been overshadowed by World War II and Vietnam, which is why it's sometimes called the Forgotten War. Yet its impact on millions of people is anything but forgotten.

Whether or not you’ve heard stories about a family member’s military experience during the Korean War, you may be able to learn more by exploring different record collections on Ancestry—draft cards, enlistment files, casualty lists, and unit histories, for example.

The Draft During the Korean War

When the Korean War began, the United States used Selective Service registration—commonly known as the draft—to build up its armed forces. This policy required all young men (but not women) between 18 and 26 years of age to register for military service. Those exempt from the draft included World War II veterans.

About 1.5 million men were inducted into military service through Selective Service during the war, accounting for a significant share of U.S. troops sent to Korea.

Military Service in the Korean War

Outside of Selective Service registration, many men—and women—chose to volunteer for service. Voluntary enlistment enabled someone to choose their branch of service, such as the Air Force or Navy.

Overall, more than 5.7 million people served in the U.S. Armed Forces during the Korean War:

- 2.8 million in the Army

- 1.2 million in the Air Force

- 1.1 million in the Navy

- 400,000 in the Marines

Soldiers served in different capacities throughout the war:

- Almost 1.8 million troops saw active duty on the front lines. There, they likely endured extreme climate conditions and the psychological strain of prolonged combat as they participated in major offensives and faced the constant threat of artillery fire.

- Support roles helped maintain vital supply lines that kept soldiers fed, sheltered, and armed—and helped hold critical ground.

- Medical units tended to the wounded while often under constant threat themselves.

Every role, from soldiers on the front lines to medics in the rear, from pilots in the seat of 4FU Corsair fighters to naval support provided by those on the USS Missouri, played a critical part in the war.

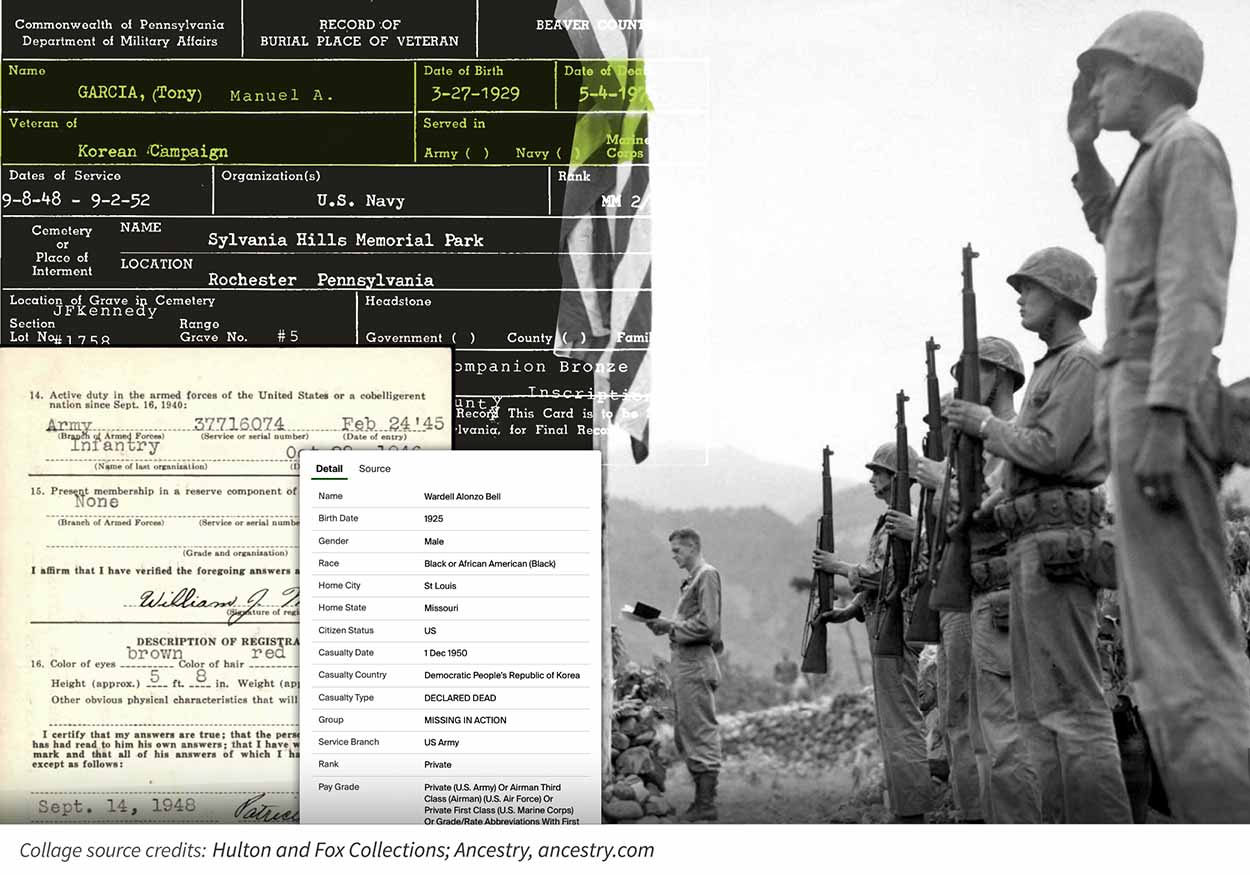

Integration of U.S. Armed Forces

Besides the Korean War’s Cold War connection, this conflict is also noteworthy as it marks the official desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces, which President Harry S. Truman mandated in 1948 through Executive Order 9981. Full implementation wasn't immediate; some all-Black units were folded into desegregated divisions, while other African American soldiers continued to serve in integrated units throughout the Korean War.

- Note: As you trace your African American veteran ancestors, you might notice race notations on older draft or enlistment records. Some rosters list whether a unit was segregated or integrated.

About 10,000 Native Americans served during the Korean War. Some were returning World War II veterans, and others were young draftees. For example, Charles Norman Shay of the Penobscot Nation in Maine served as a combat medic on the front lines in France in 1944 and was held as a POW in Germany in 1945. He then served as a combat medic in the 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division during the Korean War.

In 1948, President Truman also signed into law the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act. This Act allowed women to serve in all branches of the armed forces—the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. Women could become officers, but they weren’t allowed to command men. Women who became pregnant were dismissed. Women were also restricted to non-combat roles, except nurses and other medical specialists who were allowed in combat zones. While Selective Service registration didn’t apply to women, about 120,000 individuals still volunteered to serve in medical, intelligence, and support roles stateside and overseas throughout the Korean War.

Korean War Military Records

Tracing the movements of your veteran’s unit and learning about their experiences can help you fully appreciate the context of their service. You might uncover information that’s difficult to process, but the records you find can take on a deeper meaning when viewed through the lens of the war's immense scale and brutal realities.

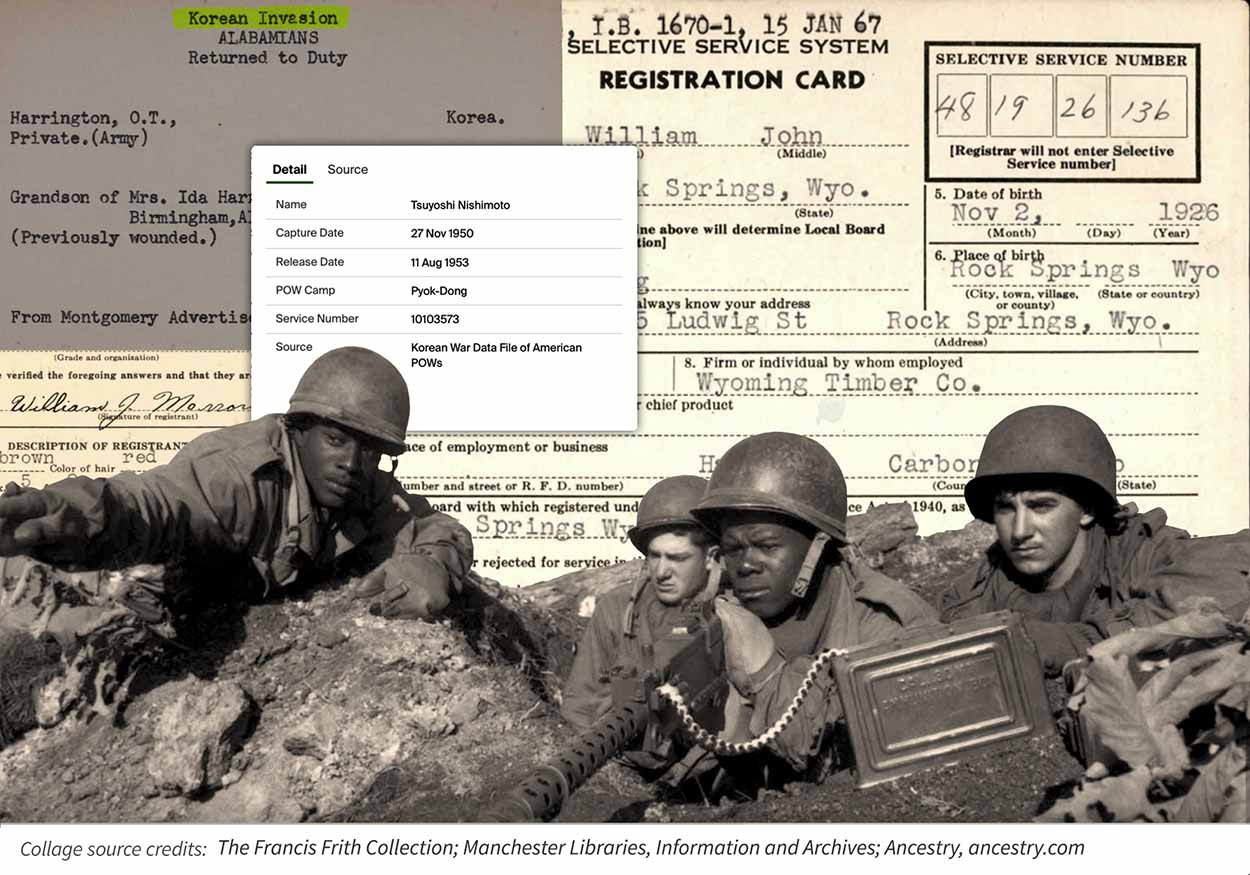

To start tracing your Korean War veteran's military history, look for their entry into service. Check first to see if you can find your family member in the Korean War Era Draft Cards (1948–1959) collection on Ancestry. Each card usually includes a registrant's name, birth date, place of birth, address, and physical characteristics. Many cards also list a contact person, such as a parent, spouse, or sibling.

Next, check to see what more you might discover by looking in these collections:

- U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958

- U.S., Navy Muster Rolls, 1949-1971

- U.S., Navy Support Books, 1901-1902, 1917-2010

- U.S., Navy and Marine Corps Registries, 1814-1992

Each record collection can contain new insights—information that may help you move forward to other records. For example, a service number or place of induction can lead you to explore unit histories. Knowing the name of the ship on which your ancestor served could lead you to the U.S., Navy Cruise Books, 1918-2009—yearbook-like records.

POW, MIA, and Casualty Records

The brutal reality of war, however, includes personal tragedies. By the time the armistice agreement was signed on July 27, 1953, U.S. casualties in the Korean War included:

- 36,000 soldiers killed in action

- 100,000 wounded

- 7,000 Americans who were captured and taken as prisoners of war

- As of May 2025, more than 4,500 are still considered “missing in action.”

Some files have been updated over time as information has become available. For example, someone initially listed as MIA might have been recovered or declared deceased decades later. Several collections on Ancestry contain information about those who suffered these fates:

- U.S., Korean War Casualties (1950-1957)

- U.S., Korean War Prisoners of War (1950–1954)

- U.S., Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Unaccounted-for Remains, Group A (Recoverable), 1941-1975

- U.S., Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Unaccounted-for Remains, Group B (Unrecoverable), 1941-1975

While these records may answer some questions about your ancestors who served during the Korean War, the information they provide may be emotionally difficult to see: they connect personal stories to actual battles and dates in the Korean War timeline. Understanding these records is essential if a relative didn't come home or avoided talking about their service.

More Ways to Learn about Your Korean War Veteran

Beyond looking at military records, other record collections and resources available on Ancestry may provide additional perspectives about your family during this period of history.

1950 U.S. Census: Taken a few months before the Korean War began, this enumeration can be a practical starting point for investigating a relative's life before the war. It can show their address, living arrangement, occupation, or marital status on the eve of the conflict. For example, a 19-year-old might appear as a student while living with parents, or a career soldier might be listed on a stateside base.

Stars and Stripes Newspaper (Pacific Editions): This publication was a daily newspaper for U.S. service members stationed overseas during the Korean War. Its pages often featured accounts of major offensives, sports scores, award announcements, or home-front news intended for deployed troops.

By searching for a relative's division or ship name, you might discover articles that mention their involvement in events such as the Inchon landing, the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge, or the Battle of the Punchbowl.

Searching by unit or military base can also lead to general updates about living conditions, ceasefire negotiations, or other moments that shaped your ancestor's time in Korea.

Local Newspapers: News publications from your soldier’s hometown might feature short articles about a particular unit, letters from the front, official casualty reports, photos of individuals departing for training, or editorial content about community support efforts.

Oral Histories: Firsthand accounts bring deeply personal perspectives to daily life in combat zones and elsewhere during the Korean War. Did your veteran leave a journal or audio recordings about their wartime service? If you’re not sure, check with other family members to see what they know. For example, they might be aware of a collection of letters in a shoebox somewhere.

If your Korean War veteran is still alive, see if they might be willing to share some of their stories. The Ancestry Memories feature can help you record them. But be mindful that your veteran may not want to talk about their experiences. For many, the subject may be too painful. As of November 2023, around 767,000 veterans who served during the Korean conflict were still alive.

Discover Your Family's Story With Korean War Records

Tracing your veteran’s story during the Korean War can be challenging but rewarding. You might start with a name or a faded photograph, but by delving into Korean War records on Ancestry, you could learn more about their service and gain a deeper understanding of their history.

Whether your ancestor was a frontline soldier enduring the bitter cold of Korean winters, a nurse who treated the wounded in a field hospital, or a worried family member who kept newspaper clippings related to your ancestor’s time overseas, every document you find can shed new light on their experience. Learning more about their history is a way to honor their service.

References

-

F4U: Corsair. National Museum of the U.S. Navy. Accessed 4 June 2025.https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/aircraft-us/aircraft-usn-f/f4u-corsair.html.

Barker, Hal. “Return To Heartbreak Ridge: A Journey Into The Past.” Korean War Project. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://www.koreanwar.org/html/return-to-heartbreak-ridge.html.

Denby, Heather A. “Korean war vet remembers French connection in 2ID.” U.S. Army. 8 July 2015.https://www.army.mil/article/151875/korean_war_vet_remembers_french_connection_in_2id.

DeSimone, Danielle. “Over 200 Years of Service: The History of Women in the U.S. Military.” USO. 28 February 2023. https://www.uso.org/stories/3005-over-200-years-of-service-the-history-of-women-in-the-us-military.

“Executive Order 9981, Desegregating the Military.” National Park Service. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/executive-order-9981.htm.

Haskew, Mike. “To Field an Army: A Short History of the Draft.” Warfare History Network. February 2008.https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/to-field-an-army-a-short-history-of-the-draft/.

“Historical Timeline.” Selective Service System. Accessed 4 Jun 2025. https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/timeline/.

“History of the Korean War.” United Nations Command. Accessed 3 June 2025. https://www.unc.mil/History/1950-1953-Korean-War-Active-Conflict.

“Induction Statistics.” Selective Service System. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/induction-statistics/.

Keeran, Joshua. “US military relied on draft-induced volunteerism.” The Delaware Gazette. 11 March 2021. https://www.delgazette.com/2021/03/11/us-military-relied-on-draft-induced-volunteerism/.

Kinney, Pat. “Iowa soldiers fought, died in first integrated units in Korea 70 years ago; many still missing.” Grout Museum District. 11 July 2023.https://www.groutmuseumdistrict.org/about/news/iowa-soldiers-fought-died-in-first-integrated-units-in-korea-70-years-ago-many-still-missing.aspx.

“Korean War.” Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home; National Archives. Accessed 3 June 2025.

Leipold, J.D. “Women veterans mark 60th anniversary of Korean War.” U.S. Army. 2 April 2013. https://www.army.mil/article/75736/women_veterans_mark_60th_anniversary_of_korean_war.

Marsh, Alan. “POWs in American History: A Synopsis.” National Park Service. 1998.https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/pow_synopsis.htm.

“Presidential Proclamation -- National Korean War Veterans Armistice Day, 2016.” Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. 25 July 2016. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/07/25/presidential-proclamation-national-korean-war-veterans-armistice-day.

“Remembering the Forgotten War: Korea.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/art/travelling-exhibits/remembering-the-forgotten-war-korea-1950-1953.html.

Schaeffer, Katherine. “The changing face of America’s veteran population.” Pew Research Center. 8 November 2023.https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/08/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population/.

“South Korea.” History.com. Accessed 3 June 2025. https://www.history.com/articles/south-korea.

“United Kingdom.” United Nations Command. Accessed 3 June 2025. https://www.unc.mil/Organization/Contributors/United-Kingdom/.

“U.S. Military Casualties - Korean War - Casualty Summary.” Defense Casualty Anaylsis System. 19 May 2025. https://dcas.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/app/conflictCasualties/korea/koreaSum.

“USS Missouri (BB 63).” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/missouri-bb-63.html.

Vergun, David. “Combat Medic Excelled in World War II and Korea.” U.S. Department of Defense. 1 November 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/Article/2786440/native-american-fought-with-distinction-in-world-war-ii-and-korea.

“Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces; Korea.” National Museum of the American Indian. Accessed 4 June 2025. https://americanindian.si.edu/static/why-we-serve/topics/korea.